Nothing Ever Happens. Buy The Fucking Dip.

This is the mantra that’s been beaten into our heads for the entirety of our investing lives. And by “our” I mean anyone under the age of 40. The Great Financial Crisis is nearly 2 decades in the rearview, and for anyone born in the mid-80’s or later, it hasn’t impacted our personal investing life in any real way. We weren’t active participants in those markets so there’s no direct scar tissue to reflect on. If anything, this naiveté has been an incredible advantage throughout our entire investing lives.

Boomers and Gen X’ers who’ve lived through a more diverse set of economic and geopolitical realities have repeatedly cautioned against blindly yeeting into the market every time there’s a correction. And why wouldn’t they? They dealt with periods of relentless inflation, a dot-com bubble that vaporized returns and a financial crisis that nearly took down the banking system.

For us Millennials and Zoomers though, you’d look like a moron today if you haven’t been full porting anytime there’s been a 10% drawdown.

I posed this question recently.

This was deliberate in a few ways. On the one hand, we are repeatedly told “keep a calm head”, “don’t get emotional”, “nothing ever happens”. So intuitively we all know what the right thing to do is. Still, knowing what to do and actually doing it are very different things1.

But what if the right thing to do is in fact, actually the wrong thing.

We’ll come back to this. But first a history lesson.

The year is 1949. World War II is over but the Cold War has just begun. The United States is the dominant global economic power and leverages its role in WWII to block Soviet access to advanced technology. It does this via something called CoCom2 which is just an informal alliance restricting strategic exports to the USSR. The gang’s all in on it (Western powers) and the goal is quite clear: limit Soviet power by choking it off from technologies that allow it to catch up militarily and economically. In typical US fashion, it gets even more aggro by passing the Battle Act (1951) which threatens to cut aid to anyone misbehaving. You help them, you’re dead to us.

Was it effective? For sure. At the time, the Soviets and China were largely self-sufficient economies that didn’t engage meaningfully in global trade. The self-isolation actually made it much easier for the Western allies to impose – and remain united in implementing – these restrictions. Export controls became a pillar throughout the Cold War and in many ways were the driving force of the Soviet Union’s multi-decade lag in technological progress.

But as Western Europe emerged from the ashes of WWII, over time the depth and scope of CoCom came under pressure. Now further removed from rebuilding post-war, these same economies sought export markets. The enforcement of a soft consensus-driven agreement was questioned and more idealistic stances became popular (“free trade can lead to reform rather than isolation”).

The Cold War export controls were a product of their time: effective at raising the cost and slowing the pace of technological progress for the Soviet Union. But truthfully, they were aided as much by the circumstances of the time: few interdependencies & marginal trade implications for European allies given how siloed their economies were. Interestingly enough, as the Cold War thawed but while CoCom was still in place, the US was butting heads with another geopolitical tech rival.

By the 1980s Japan had risen to become a technology and economic superpower, dominating important industries like semiconductors. In 1982 Japan quietly passed the US in global semiconductor market share for memory products3. Predictably this didn’t sit well with those in Washington. American officials began accusing Japan of unfair trade practices | specifically turbodumping chips below cost on world markets and closing the Japanese domestic market to foreign chips.

So Japan is kicking America’s ass in chip manufacturing efficiency. This sparks a sense of alarm in Washington over fears it was losing leadership in a critical technology that could have national security implications. Sound familiar?

The US responds how you might expect…they launch investigations and threaten sanctions. Ultimately Japan agreed to a bit of an unprecedented set of concessions as part of the US-Japan Semiconductor Agreement of 1986. The actual details of this are less important4 but what’s notable is the explicit motivation and rhetoric from the US side. It specifically “encouraged a 20% market share in Japan for US firms” and instilled monitoring mechanisms that created a level of oversight basically unheard of among capitalist allies.

“The health and vitality of the US semiconductor industry are essential to America’s future competitiveness. We cannot allow it to be jeopardized by unfair trading practices.”

You can imagine this is exactly the type of thing you might hear President Trump say today. But in fact, these specific words were delivered by President Ronald Regan in 1987.

The United States’ willingness to override free market principles in favor of strategic trade intervention is not new. And lest you think previous administrations have only talked the talk and never followed through, when it became evident Japan was not fully complying, the Regan administration slapped a 100% tariff on Japanese electronic goods. We know Trump is a show-man, but peak US-Japan trade tensions was a gaggle of giddy Congressmen smashing Toshiba products in front of the US Capitol.

“Treachery by any other name is still treachery…if it had another name, it would be Toshiba” - Rep. Helen Bentley

| A quick aside: part of this controversial display was linked to CoCom and the USSR mentioned earlier. In the mid-1980s Japan’s Toshiba (along with a Norwegian partner) covertly sold some advanced CNC milling machines to the Soviet Navy – equipment that let the USSR manufacture much quieter submarine propellers.

The scandal brought arrests and strained US-Japan relations but also revealed a shift in trade dynamics. At the end of the day, all corporations are beholden to the bottom line and where there is trade to be done and profits to be made, these actors will push the limits in service of that. This will happen with China-US trade as well. A portion of these products will find their way into the country regardless, they’ll just be more expensive. |

Japan’s response was measured and de-escalatory. Directionally speaking (and with hindsight bias) this seems obvious: Japan was an ally and hosting US troops at the time. Stoking the flames or escalating some kind of economic trade war with the US would have been silly. But this presumption carries some caveats: it assumes rational actors are the decision-makers and possess a sound grasp of economic policy. It also came at a time when globalization was expanding but supply chains weren’t nearly as complex or integrated as they are today.

Even still, the knock-on effects were complex. Protecting one sector (memory chips) affected others (PC manufacturers) in a fairly straightforward example of protectionist trade-offs. One of the core arguments that supporters of this managed trade stance made sounds a lot like what we hear today: short-term pain is justified to retain leadership and protect interests that impact national competitiveness & security.

Only China today is a very different beast from Japan in the 80s. It is a strategic rival and an ideological competitor to the US. That means all of the positioning, mediaspeak, signaling and projection of strength is happening amid far lower trust. The scale of China’s economy is obviously a lot closer to the United States’ and the two have significantly more interdependencies than anything the US & Japan shared.

And now we return to right and wrong.

What if the right thing to do is in fact, actually the wrong thing?

The right thing to do for zoomers and millennials has always been to just ignore what’s going on, buy the fucking dip and immediately be rewarded. So far, we have never had to deal with the second half of this meme5.

By my very crude observation, these are the most painful periods for anyone who started their investing career post-GFC.

2011: Eurozone Crisis

2015-16: China Devaluation & Oil Crash

2018: Fed Tightening

2020: Covid Crash

2022: Inflation + Rate Hikes

You may be thinking, damn that’s more than I thought, why are you telling me I’ve never had to endure pain? 5 of these events already!

Well let’s peel another layer of this onion. How deep were the max drawdown’s of these periods?

Not to be flippant, but the first few are borderline non-events. Sure it was a slightly different time then but a ~20% drawdown is hardly a trying moment.

Let’s add one more critical data point. How long did these events last in practice? In other words, were investors’ convictions really tested? We’ve looked at price capitulation but what about time capitulation. Specifically, how long did it take to recover previous highs?

2011: ~5 months

2015-16: ~13 months

2018: ~4 months

2020: ~5 months

2022: ~22 months

This is crazy. On 3 of 5 occasions we were back to ATH’s within 6 months. The other periods took ~1 year and less than 2 years respectively. We’re talking about the most painful periods of investing for an entire generation + and in every single case, if you knee-jerk bought the sell-off you were IMMEDIATELY rewarded.

When you compare these types of historical market events to some of the major crises that Boomers went through, it’s easy to see how and why the psychology of these two groups is so different.

Look at these Boomer events, the magnitude of the drawdowns and more importantly, the duration of the pain.

1970s Oil Shock:

S&P Drawdown: -48%

Recovery Time to Previous High: 7 years

1987 Black Monday:

S&P Drawdown: -35%

Recovery Time to Previous High: 2 years

Dot-Com Bubble:

S&P Drawdown: -50%

Recovery Time to Previous High: 7 years (tech longer)

Great Financial Crisis:

S&P Drawdown: -57%

Recovery Time to Previous High: 5.5 years

There are so many knock-on effects to these dynamics. Purely from a behavioral perspective, this is how one could crudely visualize the average investor in each group.

An oft-repeated quip is that we’re “always fighting the last war”. Something bad happens, we feel the pain, we think about what we could do next time if something similar happens. The obvious problem with this is that the next problem is likely to take a different form and so the medicine the market needs will likely be different. But for younger investors, we’ve never even really experienced a prolonged period of pain. Our brainwashed chant “buy the fucking dip” is a modern mantra, and the underlying sentiment behind it is that The Fed Will Print. No problem can’t, nay won’t, be solved by the Fed stepping in to turn the cash machine on and keep the party going.

It sounds so stupid but here’s the thing. For our entire career it’s been the right religion to practice.

But that faith has never been truly tested. Tucked away in its doctrine is a false assumption that the Fed stepping in to loosen monetary policy is a cure-all medicine that works for any economic malaise. It’s worked in the past because those ailments were easily treated with liquidity injections. The problems today are more complex and reorienting global trade is a structural shift.

You can’t just print trust between nations.

You can’t print domestic chip manufacturing supply chains.

You can’t solve fiscal dominance (while deficits are driving inflation risk) just by buying bonds.

This is why the current moment is so fun, scary, unique for an entire generation of investors. The range of outcomes has never been wider.

For Boomers though, they’ve lived through markets that weren’t easily solved with a wave of the monetary wand. Some of their formative bear market experiences required 7 years of patience to regain new highs. Imagine buying the dip for 7 years.

But Smac, you don’t get it, we’re in a new paradigm now. Markets are much quicker to react, they’re forward-looking, they price things more efficiently. Corporations are better than ever at adapting. The overton window has shifted for fiscal and monetary policy. The mask is off. The future is now old man.

That’s probably true.

But if it’s not, better to enter that world with a prepared mind…

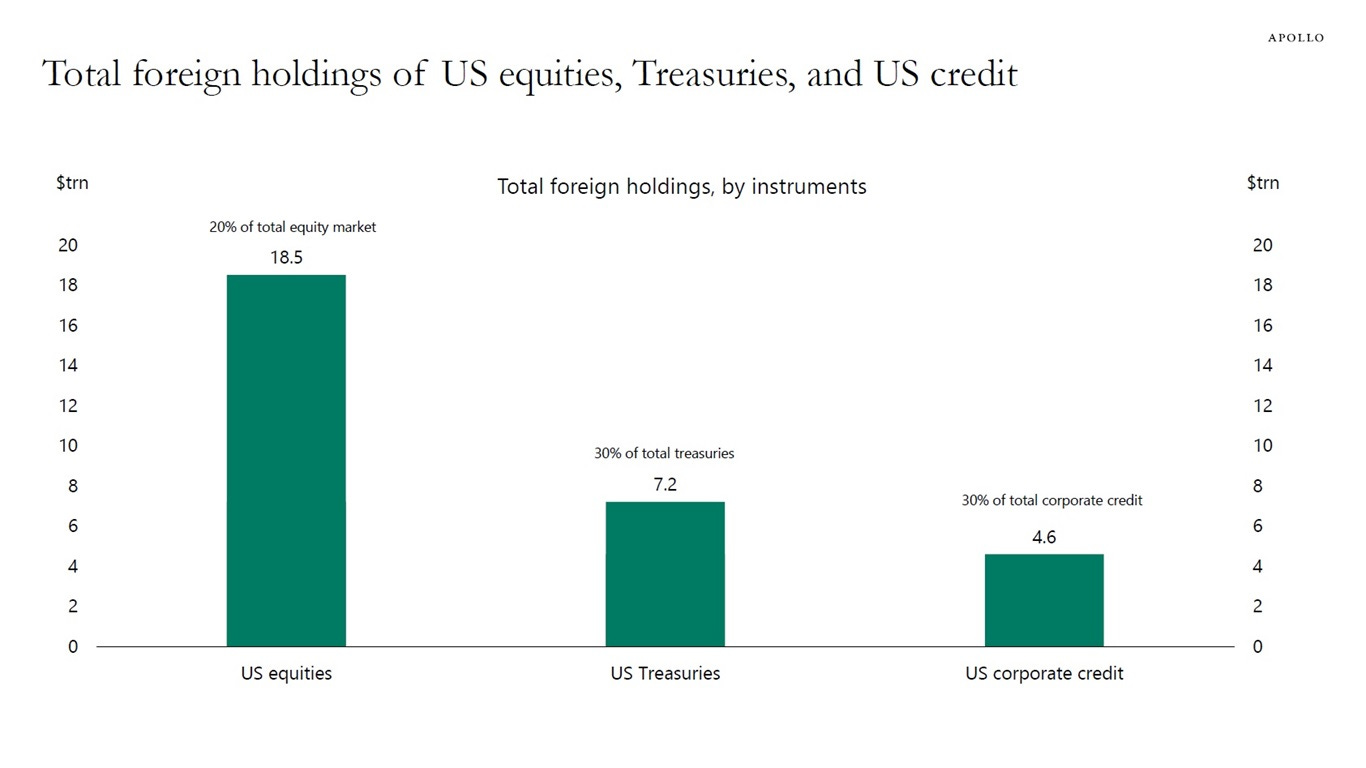

Foreign investors own between $25-30 trillion of US assets. As a country, the United States benefits tremendously from this foreign investment. Run far away from anyone telling you otherwise. Surely you’ve heard it before: the US’ best export is dollars and treasuries. Foreigners buying our assets does a few important things: it expands the multiples our companies trade at and it drives down the borrowing cost for our corporations and our individuals. So long as the United States remains the epicenter of entrepreneurship, capital formation and innovation, this will continue to be the case.

But where this trade war can spiral into something that ignites a more structural reorienting of capital markets is around how these foreign investors view the United States. The US benefits greatly from the depth of its capital markets and the rule of law protecting them. There aren’t any credible threats to this right now. But even as the US remains dominant, capital outflows from foreign investors and their marginal dollar being invested elsewhere has tangible consequences. That can bring structurally higher long-term interest rates as weaker demand for Treasuries puts upward pressure on yields. Those borrowing costs filter through the rest of the economy and tighten financial conditions. It also leads to higher baseline volatility as the natural buyer base is smaller and you’re likely to see more episodic liquidity shortages. Add on second-order effects like trust erosion, reserve managers diversifying more aggressively (i.e. into gold, non-USD currencies, commodities) & deglobalization pressures and the flywheel begins to spin the wrong direction.

The core rub here is that these developments don’t resolve themselves overnight. Jerome Powell cannot prescribe a medicine for this. And what we’ve seen thus far has been a real exodus from US assets. This hasn’t just been some technical deleveraging or a basis trade unwind. Only during the GFC did we see gold strength combined with simultaneous weakness across the DXY, SPX & the 10yr.

You also may notice that gold was rallying hard in USD terms, but was basically flat in EUR and actually down in JPY & CHF.

These aren’t pod shop level flows either. Indulge me for a second with a cringe boating analogy. If retail traders are like jetski’s (small, quick, nimble) and active funds are closer to speedboats (still fast but slightly more constrained), then these large pools of capital I’m referring to are tankers. They move extremely slow with multi-year strategic shifts that are very difficult to stop or reverse. If you’re at a sovereign wealth fund or a central bank and you’re thinking about a shift in asset allocation, that doesn’t happen overnight. You do a ton of analysis, present it to some committees, eventually present a plan to a board of directors. This type of tectonic shift doesn’t get resolved by Trump cutting tariffs on China to 60%.

It also introduces more uncomfortable questions for these allocators. Like for example, how should we be underwriting the potential for capital controls?

Your knee-jerk reaction is probably to scoff at such a suggestion. But you would have had the same reaction if someone showed you this a few months ago too.

In an extreme example, it’s not impossible to imagine the United States weaponizing its capital markets to restrict an exodus out of US assets. We’ve covered enough history today but suffice it to say, the common denominator for regimes that institute capital controls is ugly. Specifically as it relates to the US, the only times we’ve really seen this in practice is:

Emergency controls during World War I

The Gold Hoarding Ban in 1933 (by Executive Order wink wink)

Post WWII Reconstruction

Balance of Payment Controls in the 60’s-70’s

I hesitate to speculate on what capital controls might look like in a modern world (though this is some fun fan fiction if you’re interested). It’s a bit too doomer for someone who recently had to remind themselves of this.

And yet, I’ll give the TLDR anyway for the sake of completeness. The easiest version to imagine is a tax on capital flows, required ring-fencing of US dollar funding offshore, limiting repatriation of profits and quotas or required approvals that effectively penalize or otherwise restrict free capital movement. To be clear, all of these measures would be destabilizing for the United States. They would immediately rattle global allocators, force them to re-price US risk, drive risk premiums on US assets higher and erode the exorbitant privilege of the dollar.

I don’t think this is likely but lots of things I don’t think are likely happen all the time. So while I’ve largely stayed the course from earlier this year, the probability for longer-tail outcomes seems to have risen substantially. Certainly more than I anticipated. Bear porn is always dangerous because it sounds smart and sophisticated, but these people have been getting slaughtered for 2 decades. It’s possible that happens again this time. For your average retail investor, it probably does more harm than good to even consider alternatives to BTFD because re-entering the market is psychologically so difficult. But perhaps this is the point of going through these exercises | most of the time nothing happens, some of the time something serious happens. The only real sin is to not be prepared.

If they weren’t, society would be much healthier and the strain on our healthcare systems wouldn’t be so fucked.

Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls

trust but verify

great one!

This was very eye-opening, thanks for the history lesson.